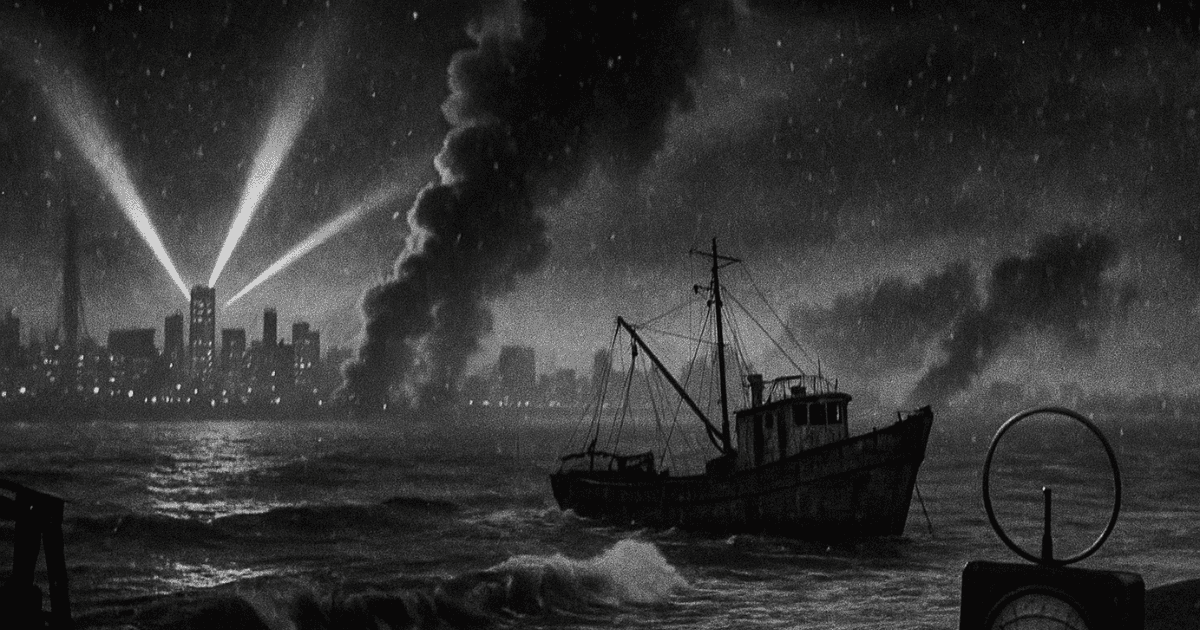

The film Godzilla, released in 1954, was more than just a monster movie; it contained a powerful message that struck a deep chord in post-war Japanese society.

Godzilla, whose peaceful existence was shattered by hydrogen bomb testing, landed in Tokyo as a figure reminiscent of the Bikini Atoll tragedy. I believe he was the very embodiment of the ‘sins of humanity,’ a manifestation of the memories of war and the fear of nuclear weapons.

While I personally adore this first Godzilla film, as the series progressed, the great king of terror gradually transformed into a ‘champion of justice,’ cheered on by children.

In this article, I will explore the trajectory of this transformation—how the king of terror became a hero—by looking back at all 15 films of the “Shōwa Godzilla Series,” from Godzilla (1954) to Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975). (Note: The Return of Godzilla (1984) is not typically included in the “Shōwa Godzilla Series”).

*This article is an English translation of the original Japanese article, 「昭和ゴジラ」の変遷を考察-ゴジラは如何にしてヒーローとなったのか?-.

Let an AI walk you through the highlights of this post in a simple, conversational style.

-

Shift from a Symbol of Terror to a ‘Fighting Monster’

The original Godzilla was a symbol of the ‘sins of humanity,’ born from hydrogen bomb tests and an object of absolute terror. However, the introduction of an opponent, Anguirus, in the next film, Godzilla Raids Again, shifted the narrative toward the entertainment-focused ‘monster vs. monster’ format, marking a crucial first step in his later heroization. -

Transformation into Earth’s Guardian: The Emergence of a ‘Common Enemy’

Initially a threat to humanity, Godzilla confronted a monster capable of communication in Mothra vs. Godzilla. The subsequent appearance of a ‘common enemy,’ the space monster King Ghidorah in Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, led him to join forces with other Earth monsters. This clearly established the archetype of Godzilla as a hero standing on the side of defending the planet. -

Establishment as a ‘Children’s Hero’ and Subsequent Changes

Godzilla effectively became a hero in Godzilla vs. Hedorah by fighting a pollution monster. In Godzilla vs. Gigan, the theme song praised him as “our Godzilla,” cementing his heroic image in both name and substance. However, once established as a hero, his role in later films became more of a plot device, leading to a dilution of his presence.

- Phase 1: As a Symbol of Fear and Destruction

- Phase 2: The Path to Heroism

- Phase 3: The Search for and Establishment of Heroism

- Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965): A Cosmic Drama and a Manipulated Godzilla

- Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966): Toward a Champion of Justice Who Strikes Down Evil

- Son of Godzilla (1967): A Shift in the Object of Human Sin and Fatherhood

- Destroy All Monsters (1968): Controlled Monsters and the Earth Defense Force

- Phase 4: The Completion and Meandering of Godzilla as a Hero

- Conclusion and the Future of the Godzilla Series

- Appendix: A List of Release Dates, Lead Actors, and Directors for the Shōwa Godzilla Series

Phase 1: As a Symbol of Fear and Destruction

Godzilla (1954): The Absolute Terror Born from the Sins of Humanity

In the very first film that started it all, Godzilla is portrayed as an object of pure terror. The premise—that an ancient creature was mutated by hydrogen bomb testing—was directly linked to the memory of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru incident, which was a stark reality for audiences at the time.

The radioactive black rain and the sight of Tokyo being destroyed and engulfed in flames may have vividly reminded viewers of the horrors of war. Godzilla was the personification of uncontrollable violence that humanity had created with its own hands, and he showed no hesitation or sentimentality in his destruction (one could say he was “just living”). It was as merciless as a natural disaster, and at the same time, it appeared as a clear “punishment” for humanity.

The depth of this work lies in the fact that the means to defeat Godzilla also heavily reflects the “sins of humanity.”

The “Oxygen Destroyer,” invented by Dr. Serizawa, was the only hope for vanquishing Godzilla, but it was also a demonic weapon that could potentially surpass the hydrogen bomb. Fearing its misuse, the doctor chooses to end his own life along with Godzilla.

The light and shadow of scientific progress, and the grim reality that one must commit further sins to atone for past ones. The original Godzilla had a strong element of social drama, sharply indicting the fundamental contradictions and guilt borne by humanity through the existence of Godzilla.

Of course, in this original Godzilla, there is not a single trace of ‘Godzilla as a hero.’.

Godzilla Raids Again (1955): The Appearance of an Opponent and a Shift in Narrative Structure

Released just six months after the massive success of its predecessor, this second film in the series arguably set the course for the series’ direction (one could also say it gave the “Godzilla series” a new path).

The biggest change was the introduction of another monster, “Anguirus.” This shifted the narrative structure from a simple “Godzilla vs. Humanity” formula to one centered on the clash between monsters, “Godzilla vs. Anguirus.” Until the 1984 The Return of Godzilla, no other film would feature Godzilla alone.

With Godzilla having an “opponent to fight,” the destruction of cities evolved from being a “one-sided rampage by Godzilla” to having the aspect of being the “aftermath of a fierce battle between monsters.” This can be seen as the dawn of the monster-wrestling style of entertainment, later exemplified by series like Ultraman. Before the battle of the two behemoths, humanity could do nothing but flee in terror. This setup had the effect of relativizing the threat of Godzilla.

However, at this point, there was still no hint of his heroization. Both Godzilla and Anguirus were ‘children of the atomic bomb,’ awakened by hydrogen bomb tests, and they remained equal threats to humanity. The fundamental view of the monsters followed that of the first film, and the story’s conclusion was merely a temporary solution: burying Godzilla alive in a mountain of ice.

Nevertheless, the format of “another monster opposing Godzilla” was undoubtedly a crucial first step that would allow Godzilla to transform into a hero in the later series.

Phase 2: The Path to Heroism

King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962): A Symbol of the Shift to Entertainment

Released after a seven-year hiatus, this was the first film in color. The very concept of a showdown between American and Japanese monster stars clearly signaled a shift away from depicting social issues like the “scars of war” and the “threat of nuclear weapons” toward pure mass entertainment (which is perfectly fine in its own right).

The King Kong featured in this film is a giant ape from a South Seas island, unrelated to nuclear weapons. The appearance of a “monster not born of nuclear power” relativized the specific association of Godzilla (and “monsters” in general) with the “nuclear threat.” It established that a “monster” did not necessarily have to be linked to the “nuclear threat.” In that sense, this film can be called a major turning point for the Shōwa Godzilla series.

Of course, the imagery of “Godzilla and the nucleus” is maintained, as seen in the depiction of Cherenkov radiation when Godzilla emerges from an Arctic iceberg. However, the story’s main focus is on the wrestling-style confrontation between the two giant monsters, and the heavy atmosphere of the original is diluted.

The human characters, including the protagonist Osamu Sakurai played by Tadao Takashima, are portrayed comically, and the entire film maintains a lighthearted tone. Godzilla is no longer a being burdened with a social message but is beginning to be treated as a powerful character to liven up the entertainment.

Furthermore, from this film onward, Godzilla is never explicitly defeated. Instead, the stories conclude in a somewhat ambiguous manner, such as him “returning to the sea after a battle.” While this might have been a commercial decision to facilitate sequels, it can also be seen as Godzilla changing from an “absolute evil that must be destroyed” to something akin to a “perpetual natural phenomenon.”

Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964) & Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964): The Emergence of Personality and a Common Enemy

These two films are critically important in discussing Godzilla’s heroization for the following two reasons.

- The Budding of Personality: In Mothra vs. Godzilla, for the first time, Godzilla confronts a “monster capable of communicating with humans.” Although it’s through the Shobijin of Infant Island, Mothra has a clear “will” and can converse with humanity. Mothra’s motivation—fighting to protect her egg—stands in stark contrast to Godzilla, who until then seemed to act solely on an instinct for destruction. This moment, when a “personality” was given to a monster, laid the groundwork for Godzilla himself to be given more complex emotions and roles in later films.

- The Appearance of a Common Enemy: In the following film, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, a threat to the entire planet arrives from space: “King Ghidorah.” This concept of an “extraterrestrial invader” was groundbreaking. King Ghidorah becomes a common enemy not only for humanity but also for Godzilla and Rodan. Then, an astonishing (and depending on your view, comical) scene unfolds where Mothra persuades the two monsters. Ultimately, the development where the Earth monsters, who were previously enemies, team up to fight King Ghidorah hinted at a 180-degree shift in Godzilla’s position.

Godzilla, once a menace to humanity, ends up siding with the defenders of Earth against a more powerful “external enemy.” Here, the prototype of Godzilla as a hero can be clearly seen.

Of course, at this stage, he had not yet become an ally of humanity. However, it was undoubtedly a major step in Godzilla’s transformation into a multifaceted being, not just a simple god of destruction.

Phase 3: The Search for and Establishment of Heroism

Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965): A Cosmic Drama and a Manipulated Godzilla

This film is somewhat unique in terms of Godzilla’s positioning. The story expands to Planet X, a satellite of Jupiter, and humanity has achieved a level of technology that allows for free space travel.

At the request of the Xiliens, who are suffering from King Ghidorah’s attacks, Godzilla and Rodan are “loaned out” to fight for them. However, this is all a trap as part of the Xiliens’ plan to invade Earth.

In this work, Godzilla loses his agency and is depicted as a “weapon” or “victim” conveniently used by the Xiliens. The drama of the humans (and aliens) takes center stage, and Godzilla’s screen time is extremely short.

However, this story provided an opportunity to re-contextualize Godzilla’s existence from a planetary to a cosmic scale, and it also served as a starting point for his role as a “guardian of Earth fighting against invaders from space,” a theme that would be revisited many times.

Furthermore, the “Shē” pose that Godzilla strikes on Planet X can be seen as a symbolic scene of his advancing personification and humanization. Personally, it’s a scene I’m very fond of (even though I think it denies Godzilla of being Godzilla).

Excluding the original Godzilla, Invasion of Astro-Monster is personally my favorite film in the “Shōwa Godzilla Series.”

By today’s standards, the design of the “Xiliens” is rather comical and funny, and as a result, one might even call it avant-garde. It’s something you can’t really watch properly without “mentally preparing” yourself.

However, I find the story clever in how they use Godzilla and Rodan to advance their invasion of Earth while minimizing their own casualties. As a result, the existence of aliens and Godzilla coexist naturally.

I also think it’s smart how the romance between Glenn and Namikawa succinctly illustrates the “inevitable defeat of the Xiliens, who make decisions via electronic calculators (or AI, in modern terms).” (In other words, the power of love!).

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966): Toward a Champion of Justice Who Strikes Down Evil

This film and the next, Son of Godzilla, cleverly separate Godzilla from the element of “destroying human society” by confining the story to a remote island, far from civilization (I think this was also a reflection of such a fact becoming “common knowledge” for viewers). This fact, perhaps unintentionally, greatly advanced Godzilla’s heroization.

In Ebirah, Horror of the Deep, Godzilla’s opponent is not just the monster Ebirah. The true enemy is the secret organization “Red Bamboo,” which manufactures nuclear weapons at its island base. It is extremely interesting that “nuclear power,” the very cause of the original Godzilla’s creation, is depicted here as a “symbol of evil” for Godzilla to crush. Godzilla punishes the “humans who misuse nuclear power” and, as a result, becomes a savior for the protagonists. He is no longer a threat to humanity but a natural enemy to specific evil-doers and a reliable ally for good citizens. This dynamic was clearly established here.

Son of Godzilla (1967): A Shift in the Object of Human Sin and Fatherhood

In this film, the backdrop is a “global food crisis,” and as a solution, a “weather control experiment” is conducted, setting a new “human sin” as the theme. The failure of this experiment leads to the appearance of giant mantises and a giant spider, throwing the island’s ecosystem into disarray. The theme moves a step beyond the “nuclear” issue of the original Godzilla, broadening its scope to a wider critique of civilization.

The most distinctive feature of this work is the appearance of Godzilla’s son, “Minilla.” Godzilla shows a paternal side, protecting Minilla and teaching him how to fight. Through this, Godzilla becomes not just a combat creature but a being with human-like emotions such as love and protectiveness, making him an easier character for the audience (especially children) to empathize with.

Amidst the crisis of abnormal weather caused by humanity, Godzilla’s fight to protect his child also ends up helping humans, further strengthening his image as a guardian.

Destroy All Monsters (1968): Controlled Monsters and the Earth Defense Force

In this film, which can be considered a culmination of the Shōwa series, the setting is the late 20th century. Human science has advanced dramatically, and monsters, including Godzilla, are managed and studied at “Monsterland” on the Ogasawara Islands. Godzilla is depicted as a being that is no longer a threat to humanity.

The story begins when the Kilaaks, aliens plotting to invade Earth, take control of the monsters and have them attack cities worldwide. Humanity breaks the mind control and, with the monsters on their side, launches a counterattack against the Kilaaks. Godzilla, as the leader of the Earth monster army, faces King Ghidorah in a final battle.

By this film, Godzilla has completely established his status as a member of the “league of heroes protecting the Earth.” The structure of humans and monsters fighting together to repel invaders from space is so far removed from the original that finding traces of it is a challenge.

Phase 4: The Completion and Meandering of Godzilla as a Hero

A Key Transitional Film: All Monsters Attack (1969)

While there is a significant gap in the portrayal of Godzilla between Destroy All Monsters and the next film, Godzilla vs. Hedorah, this unconventional work symbolizes that change. The setting of this film is a real-world Japan where monsters do not exist. Godzilla and Minilla are depicted as figures of admiration in the dreams of the protagonist, a bullied boy named Ichirō.

In his dreams, Godzilla is an ideal hero who gives Ichirō courage and teaches him how to stand up to bullies. Minilla even appears as a “friend” who shares the same troubles as Ichirō. By separating Godzilla from the real world and making him an inhabitant of a boy’s fantasy, the negative image of “destruction” is completely eliminated.

By portraying Godzilla as a pure “object of admiration” and “champion of justice,” the psychological groundwork was laid, so to speak, for depicting Godzilla as a complete hero in the real world in subsequent films (though I doubt this was an intentional psychological preparation).

Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971): The Substantial Achievement of Heroization

This is the film where Godzilla was substantially established as a hero. The enemy, Hedorah, is a pollution monster born from a mineral from space that absorbed pollutants discharged by humans. Its very existence is a legacy of the dark side of rapid economic growth—a lump of “human sin” (the sad reality behind the nostalgic “Always: Sunset on Third Street” era!).

Originally, Godzilla has no obligation or reason to fight Hedorah, a creature born from humanity’s own doing. However, Godzilla suddenly emerges from the sea and engages in a life-or-death battle with Hedorah on behalf of humanity. His entrance scene is highly symbolic, as if he were a “guardian deity” appearing in response to the people’s suffering and wishes.

Although set on the Japanese mainland, there is almost no depiction of urban destruction by Godzilla. Instead, his relentless pursuit and annihilation of Hedorah make him look exactly like an enforcer of justice. As a transcendent being who purifies humanity’s follies, Godzilla’s heroism became definitive here.

Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972): A Hero in Both Name and Substance

Having become a de facto hero in the previous film, Godzilla’s status is elevated to an undeniable one in this work. The story involves Godzilla and Anguirus confronting the cyborg monster Gigan and King Ghidorah, sent by the M Space Hunter Nebula Aliens who are plotting an invasion of Earth under the guise of peace.

Two points are particularly noteworthy in this film. First, a scene was inserted where Godzilla and Anguirus converse like humans using “speech bubbles.” This is the pinnacle of the character’s personification, showing that Godzilla had completely become a character seen from a child’s perspective.

The second point is the theme song “Godzilla March” that plays at the end. The lyrics, “Go, go, our Godzilla,” are clearly in support of Godzilla. This can be seen as the production side officially declaring Godzilla as a “hero for children.” This is the moment Godzilla became a hero in both name and substance.

Deepening and Formalization of the Hero Route: From Godzilla vs. Megalon (1973) to Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975)

Having been perfected as a hero, Godzilla enters a period of aimlessness where his very reason for being is questioned.

- Godzilla vs. Megalon: Co-starring with a more straightforward hero, the electronic robot “Jet Jaguar.” Godzilla plays the role of a sidekick who rushes to Jet Jaguar’s aid, and his presence is diminished.

- Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla: A robot monster, “Mechagodzilla,” disguised as Godzilla, appears. The real Godzilla challenges Mechagodzilla alongside the legendary monster King Caesar. However, he is defeated in the first battle, and his absolute strength begins to show cracks. The protagonist of the story is rather King Caesar, with Godzilla being just one of the heroes in a joint front.

- Terror of Mechagodzilla: A revenge match from the previous film. The focus is on the tragic drama of the villain, Dr. Mafune, and his daughter, Katsura. Godzilla’s role is reduced to that of a device for destroying the invaders’ weapon. While Katsura’s cyborg transformation shows a return to the theme of the sins of science, it is not linked to Godzilla’s existence, and the necessity of it being Godzilla is lost.

Because he was perfected as a hero, Godzilla became a convenient “device” to move the story forward, losing the overwhelming presence and charisma of the original. The end of the Shōwa Godzilla series may have been a fate that awaited at the end of the path of heroization.

Conclusion and the Future of the Godzilla Series

Godzilla, born as a symbol of “human sin” in the first film, underwent a major transformation in his role, starting with gaining a “fighting opponent” in Godzilla Raids Again. As the series progressed, the enemies shifted from internal threats on Earth to invaders from space and monsters created by pollution. In the process, Godzilla gradually developed a “personality” and threw himself into the fight to protect the community of Earth.

His dialogue with the communicable Mothra and the battle against the “common enemy” King Ghidorah showed that Godzilla was not merely a god of destruction and paved the way for him to become a hero. Then, in Godzilla vs. Hedorah, where he fought the pollution monster symbolizing humanity’s self-inflicted problems, Godzilla effectively established his identity as a hero protecting humanity. Furthermore, with the theme song proclaiming him as “our Godzilla” in Godzilla vs. Gigan, that hero image was solidified in both name and substance.

Godzilla’s transformation in the ‘Shōwa Godzilla Series’ was a process of one being rewriting its meaning from “terror” to “justice” while sensitively reflecting the atmosphere of the times. This trend came to a halt with Terror of Mechagodzilla, but after about a decade, Godzilla was revived as a “king of terror” in the 1984 The Return of Godzilla and would follow a roughly similar transformation in the “Heisei Godzilla Series” (though not as blatant as in the “Shōwa Godzilla Series”).

Moreover, this trend has been adopted by the Hollywood versions of Godzilla. While Gareth Edwards’ 2014 GODZILLA adequately depicted the “destructive god” aspect of Godzilla, in the 2024 Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire, Godzilla seems to have developed a personality, there are plenty of comical depictions, and he fights alongside Kong against a common enemy of humanity.

Thinking about it this way, it becomes clear that the so-called “Millennium Series” is an outlier among the “Godzilla Series,” but I’ll consider that some other time.

Also, Shin Godzilla and Godzilla Minus One are works that fall within the legitimate lineage of the “original Godzilla,” so if you’re looking for the “original-like” quality in Godzilla, you’d turn to these films (and the ‘84 Godzilla).

Personally, the original Godzilla is my favorite, and I don’t particularly feel the need for new installments. Nevertheless, I have seen (and liked) all the Godzilla films, and somewhere in my heart, I harbor the ambivalent feeling of looking forward to a new one.

I think there’s an aspect of becoming an unforgettable presence by continuing to create, so perhaps there is meaning in new films being released, just so we don’t forget the masterpiece that is the “original Godzilla.” Even if that new film portrays “Godzilla as a hero.”

The above is my personal take on the “transformation of Godzilla in the Shōwa Godzilla Series.” Of course, there may be differing opinions, but I believe this is generally the path Godzilla took to become a hero.

As I mentioned in the article, the brilliance of the original Godzilla is immense, but I basically like them all (at least, there are no films I dislike).

If you’d like, please tell me your “favorite Shōwa Godzilla film” in the poll below.

Appendix: A List of Release Dates, Lead Actors, and Directors for the Shōwa Godzilla Series

*All links go to Wikipedia articles

| Film Title | Release Date | Lead Actor | Director |

|---|---|---|---|

| Godzilla | November 3, 1954 | Akira Takarada | Ishirō Honda |

| Godzilla Raids Again | April 24, 1955 | Hiroshi Koizumi | Motoyoshi Oda |

| King Kong vs. Godzilla | August 11, 1962 | Tadao Takashima | Ishirō Honda |

| Mothra vs. Godzilla | April 29, 1964 | Akira Takarada | Ishirō Honda |

| Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster | December 20, 1964 | Yosuke Natsuki | Ishirō Honda |

| Invasion of Astro-Monster | December 19, 1965 | Akira Takarada | Ishirō Honda |

| Ebirah, Horror of the Deep | December 17, 1966 | Akira Takarada | Jun Fukuda |

| Son of Godzilla | December 16, 1967 | Tadao Takashima | Jun Fukuda |

| Destroy All Monsters | August 1, 1968 | Akira Kubo | Ishirō Honda |

| All Monsters Attack | December 20, 1969 | Kenji Sahara[1] | Ishirō Honda |

| Godzilla vs. Hedorah | July 24, 1971 | Akira Yamauchi, in Japanese | Yoshimitsu Banno |

| Godzilla vs. Gigan | March 12, 1972 | Hiroshi Ishikawa, in Japanese | Jun Fukuda |

| Godzilla vs. Megalon | March 17, 1973 | Katsuhiko Sasaki | Jun Fukuda |

| Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla | March 21, 1974 | Masaaki Daimon | Jun Fukuda |

| Terror of Mechagodzilla | March 15, 1975 | Katsuhiko Sasaki | Ishirō Honda |

- [1]

- Kenji Sahara is listed based on the order in the opening credits, but he played the father of the bullied boy, Ichirō Miki. Ichirō was played by Tomonori Yazaki.

About the Author

Recent Posts

- 2025-10-02

An Analysis of the Shōwa Godzilla’s Transformation: How Did Godzilla Become a Hero? - 2025-10-01

Godzilla(1954):Full Synopsis and Analysis: The “Sin” and “Destruction” Symbolized by Dr. Yamane and Dr. Serizawa - 2025-09-30

Godzilla (1954): Dr. Serizawa’s Love and His Suicide with the Monster - 2025-09-28

Princess Mononoke: What Did Ashitaka Mean by “The Forest Spirit Can’t Die. It Is Life Itself”? - 2025-09-27

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: Full Synopsis & Analysis: Why Did E.T. Collapse by the River and Come Back to Life?